Jeremy Chapman pays tribute to Muhammad Ali on his 70th birthday

“How the Greatest taught me harsh lessons on gambling and Monopoly”

“How the Greatest taught me harsh lessons on gambling and Monopoly”

NOT everyone knows this but Henry Cooper wasn’t the only Englishman to lose twice to Cassius Clay/Muhammad Ali, the sporting legend they call The Greatest who celebrates his 70th birthday today.

I, too, suffered two terrible reverses. A heavy points defeat on the Monopoly board when interviewing the great man in his hotel suite before his first fight with Cooper in 1963 (well, I thought it was the wisest thing to do if I wanted to get out in one piece), but comprehensively out for the count when Clay, as he then was, won the world heavyweight championship from Sonny Liston some eight months later.

Let me explain. I laid Clay at 100-1 (as against the bookmakers’ price of 7-1) to my sports editor on the Buckinghamshire Advertiser and lost the equivalent of two months’ pre-tax wages at the time, a sum I had no chance of paying as my entire savings amounted to just £14.

Luckily, he gave me a year to pay it off at £2 a week but my first, ball-breaking crack at being a bookmaker taught me two key lessons for later life: don’t believe all you read and don’t even believe all you see.

Having seen Clay knocked down by little Cooper (they had to put lead in his boots to get him up to 13st 3lb) and trailing on points before cutting Our ‘Enery to ribbons in round five, I, as a cocky 22-year-old who fancied himself as a boxing judge, figured he had no chance against Liston, the ugliest, baddest man on the planet, reckoned to be a killer not only in the ring but out of it, and an unbeatable champion run by the mob.

But never believe the type in boxing, it’s aimed at selling tickets and often bears little relation to the truth.

When it came to it, Sonny was a slow, ponderous plodder who could barely lay a glove on Clay and quit on his stool at the start of round seven with an alleged shoulder injury.

In the rematch he lay down in round one to a punch nobody saw.

Being an innocent abroad, I had also not realized that Cooper was hand-picked for Clay because he was what’s known in the trade as a bleeder, a fighter who gets a cut eye if you sneeze, and the young American, whose speciality was predicting the round in which he was going to finish it, needed to rebuild his reputation after a New York disaster against Doug Jones, tipped by Clay to “fall in four” but in the end only a disputed points loser.

Gullible and naïve as I was, I totally failed to realize that for most of the Wembley fight, Clay was a serious non-trier. He wanted to give London a good first look at him and called it for round five.

So he messed around, allowing Cooper to steal some of the early rounds and then got careless at the end of the fourth, resulting in that famous knockdown punch that made a man who was never a front-rank heavyweight into a national hero.

Given a few precious extra seconds to recover because of a torn glove, Cassius then came out showing his full bag of tricks, looking entirely different class to the overwhelmed Londoner, and the fight was over in a flash with Cooper’s eyes a pitiful, hideous mess.

That game of Monopoly? Thereby hangs another tale. Having watched Cassius train for the fight at White City, I had bluffed my way into arranging an interview with him by saying I was from Boxing News (sounded much better than trainee reporter on a weekly paper) and, on arrival, was instructed to play Monopoly with him and two delightful young ladies wearing not a lot of anything except perfume, while I was asking my questions.

I can still hear Clay saying, “Man, you do have some weird names in your country – Ly-ses-ter Square, how do you say that?”

We were just two kids together having a laugh – it was a few months before he changed his name to Muhammad Ali, and long before he refused to fight for his country, saying: “ I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong. I’m not going to Vietnam to help bomb brown people when black people back home in Louisville are being treated like dogs.”

And although he had been Olympic light-heavyweight champion at 18, I did not fully realise I had been in the presence of greatness.

The ‘interview’, of course, never appeared. Who in south Bucks wanted to read about Clay (even I could not invent a Buckinghamshire connection) when there was Chiltern Table Tennis League secretary Bob Brown’s weekly review on the sports pages and a fine picture of Chesham Bois Women’s Institute’s Chutney and Pickle Fayre on Page Three?

Great and beyond great, as it turned out, Ali made boxing respectable after the shady Liston era in becoming the most charismatic human being not only in the fight game, not only in sport, but the whole world.

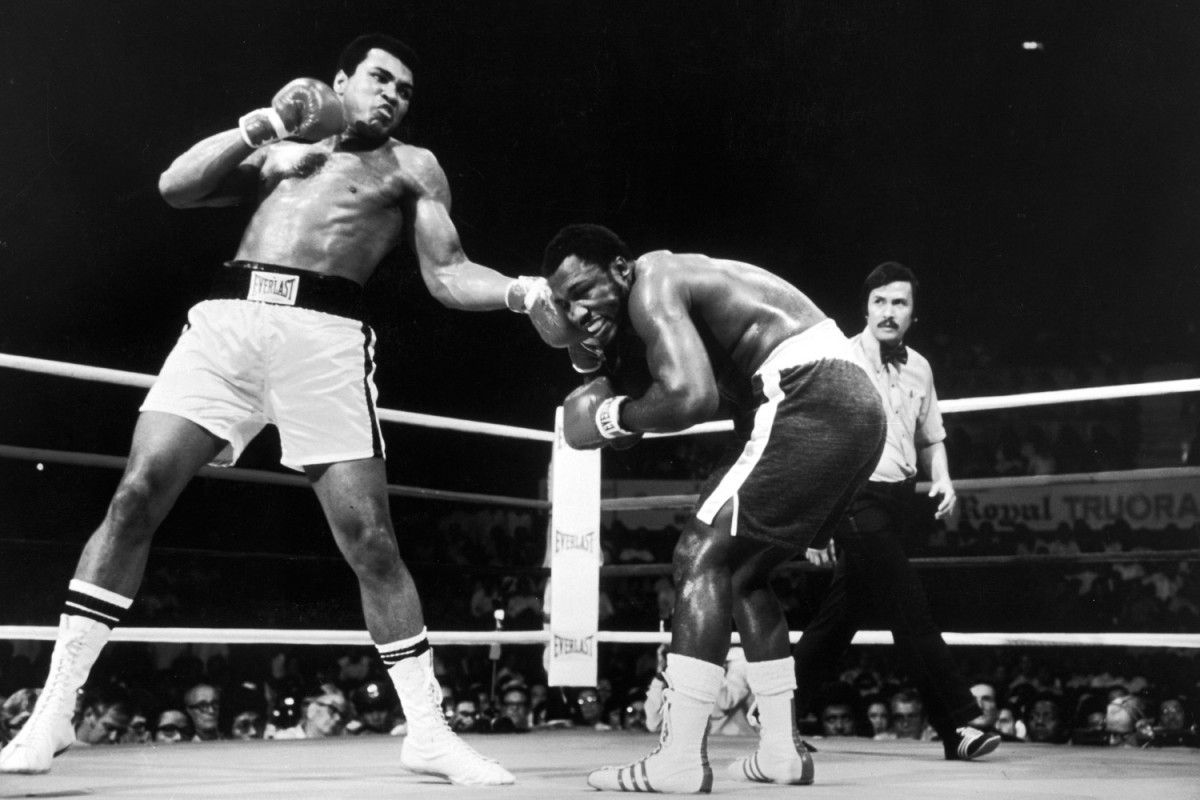

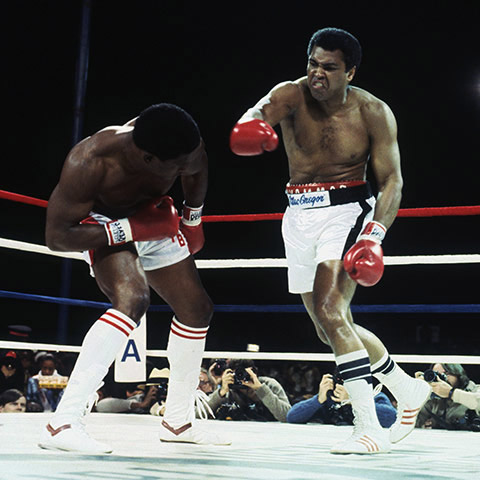

FILM STAR handsome, with the ability to go on chat shows and charm the pants off everybody, he turned boxing into the beautiful art not only with the dazzling speed of his footwork but also the fighting heart that saw him become three times a world champion, survive three wars with Joe Frazier and, as a 7-2 underdog in this greatest moment of triumph long after his dancing legs had gone, kid the ferocious George Foreman to a knockout defeat in the Rumble in the Jungle.

On the canvas for a total of no more than six seconds of a 61-fight career stretching from 1960 to the sad creature who bowed out to Trevor Berbick in 1981, his famous phrase “Float Like A Butterfly, Sting Like A Bee” forever has a place in sporting lore.

The story about him I like best comes from human punchbag Chuck Wepner, a 40-1 no-hoper but one of the four who knocked him over (although Ali claimed he stood on his foot), relates that he bought his wife a blue see-through negligee on the morning of the fight, saying: “You put this on tonight, honey, because you’ll be sleeping with the heavyweight champion of the world!”

After poor Chuck, supposedly the model for Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky, had been battered for 15 gory rounds, Mrs. Wepner responded: “Am I supposed to go to his hotel room or is he coming to mine?”

Even when he began slurring his words and eventually got diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, the one thing Ali never lost was his great chin.

But he lost most of his speed and all his punch. The last man he put down, in a Munich mismatch, was Richard Dunn, one of the worst British heavyweight champions ever, and he had seven more fights after that.

In the second-last, he failed to win a round against WBC champion Larry Holmes, who idolized Ali and claims he took it easy until the old man was retired after round ten.

Parkinson’s, diagnosed four years later, was just around the corner but Ali was still able to light the Olympic flame at Atlanta in 1996, do other great work for world peace, and, miracle of miracles, he’s still alive today, hopefully still able to enjoy the lavish celebrations taking place in his home city of Louisville.

All sport raises a glass of the finest vintage to a great ambassador for sport and life itself.

Is has been a privilege to have been around when you have, “Cash”, and to have seen you at your very best.

So many thanks for so many memories.

This article first published on 17th January 2012 and has been provided by and approved for publication on this website by Jeremy Chapman